In a webinar with Stifel Managing Director of Research David Ross, Steve presented the results of our annual survey of transportation executives. Following is a lightly edited excerpt.

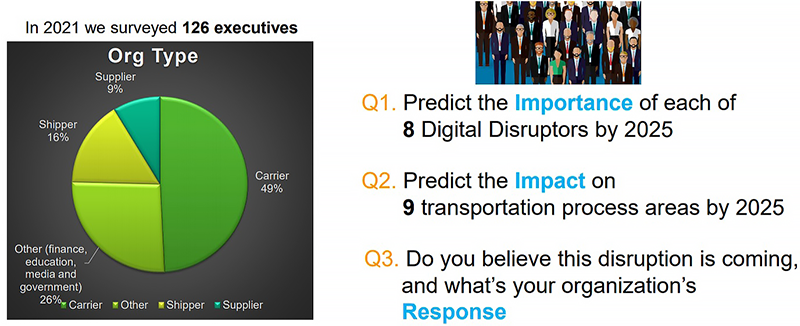

This year, we were pleased to get 126 responses, about half from executives at carriers, 3PLs and brokers. For eight disruptors, we asked “By 2025, will it have 1) essentially no real impact on freight transportation? 2) limited impact in small niches? 3) moderate impact, particularly at the high end? Or 4) a large impact and be very common?”

Regarding self‑driving trucks, executives were the most skeptical, although there is a huge, solid business case. Drivers are roughly a third of the transportation cost. Assuming that while the vehicle is self-driving, it does not burn hours of service, then you could essentially make a single-op run at the speed of a team. There are also encouraging tailwinds. The automakers and tech firms like Apple are making massive investments and partnerships in software and the necessary hardware. Self‑driving private cars are paving the way, pun intended, both on the tech-cost side and on public acceptance. Finally, many US government officials see this as a grab‑it‑or‑lose‑it economic opportunity.

Blockchain is really two different things: cryptocurrencies and digital ledgers, the latter of which make a lot of sense for the freight community. With the blockchain model, a good foundational technology right now is The Linux Foundation's Hyperledger Fabric. A private blockchain is a series of known nodes that agree to cooperate. For example, in railroading or airlines, you would say that the class I railroads, and the major airlines will each operate a node. Arguably, it’s going to make tracking harder. The private model is based on the fact that we're going to have known nodes and then permission people in creating a lot of efficiencies. The downside for our community is that you have to get all the participants to adopt the same technology and message standards. The challenge is that the U.S. is wildly disaggregated and, in many cases, colossally manual, including scanning PDFs of bills of lading and returning them to the company that issued them.

Regarding drones, three of the primary use cases are: inspections, local deliveries, and commercial delivery. Railroads already use drones for track inspections. You can use LIDAR, which can see in the dark, on sensors, which is neat. There are still pretty severe limitations due to the conditions in which these vehicles operate, and flight time limitations. Because these products are on a rapid evolution, every year at this consumer level, we see a brand-new generation of these things that are faster and better. For local deliveries over one’s own property, there are very strong use cases. For example, delivering chemicals like pesticides: rather than spraying the entire field, the drone could figure out where it is needed most. For another, at campuses or hospital complexes, drones are moving things from one building to another, rooftop to rooftop. In commercial delivery, thanks to changes in government regulations, UPS was the first to go full bore and create a certified airline. I color them “green” because they also have the advantage that they have all the brown vans all over the streets—a perfect platform to launch and land the drones from. Alphabet and Amazon are in the game, too. Lastly, COVID has changed residential delivery norms. One of the original ideas of drones was how you link to the signature capture. We don't expect signature captures anymore and in fact we prefer contactless in many cases. People are looking more and more for online everything. Maybe my test kit will be dropped by a drone at my front door, so I don’t have to go to the drugstore—I think that’s very positive.

Electric trucks. 35 percent of our survey respondents said it would have a moderate or large impact in the next four years. We’re much more bullish on short-haul. The electric vehicles seem very reasonable for many first Model S applications like package LTL. The environmental benefits are going to be very green-friendly for consumers and politicians, particularly in fleets, in cities and suburban neighborhoods. Often these deliveries, they cube out rather than weigh out. There’s lots of stop and start and most importantly, I think the trucks for local fleets return to a common depot—which is great for charging and also allows a company to roll this out regionally. By contrast, I think long-haul has more headwinds. It's a commodity business that the consumer rarely sees, so it's all about the dollars. A current diesel Class A tractor can go anywhere, haul any load. Typical questions: “Will Class A EV’s be as flexible? How heavy are these batteries and hydrogen cells?” Right now, they’re heavy--can they get light? Until they do, a lot of long‑haul loads hit max weight limits. Also, are there non‑congested recharging stations and repair facilities in all the right places? On the other hand, on a positive note, some large shippers have publicly committed to reducing their carbon footprint. While the consumer might not be directly seeing a large truck on load, they certainly see them on the highways.

My colleague Keith Dierkx suggested we add to our survey this year “platform aggregators” that connect multiple data networks into a single source of truth. Examples are project44 and FourKites and TradeLens. There is a new project called RailPulse, which is Internet of Things on rail cars, with a target to have 20 percent of the rail cars in North America tagged. On the plus side, for every over-the-road, door‑to‑door shipment, about 15‑20 percent of the of the cost is back office administration on both sides, which includes arguing over accessorials, and the whole show. Carriers waste a lot of capacity, trailers are not full, deadheads, driver dwell, underutilized equipment--data aggregators might be able to help. On the minus side, the data aggregators claim you can see everything in one place. This requires every participant to connect to the aggregator and keep the data up‑to‑date, which is a big ask. I think a lot of these platforms feel that if you can just get visibility on all your freight, or all your assets, that would be the end state. What we want to do, I’d say, it's not just to see things, but to choose the best actions. A little call out to optimization, which we’re big proponents of. Visibility is a nice step on the way, but it’s about optimization.

Digital marketplaces: 62 percent were in favor of that as being moderate or large impact in the next four years. Is the capacity and price discovery going to be online or off? If you really want to know the cost of going in and out of a lane, short term or long term, the digital marketplace is where you go to find out and actually make those bookings. There are reasons for doubt and reasons for optimism. Some of the reasons for doubt are that Truckstop.com and DAT are great companies that have been around a long time, and there have been hundreds of competitors that have come and gone over the years. There is a constant set of startups trying to enter this space. Adding confusion, most of the brokers I know are calling themselves e‑brokers and touting the automated freight matching. A barrier is that annual contract rates are still dominant for many shippers and carriers. Some reasons for optimism. Every person who works at a carrier or shipper is also a consumer. As consumers, we’re increasingly getting used to and demanding the convenience of an Amazon, Airbnb, Expedia, and Uber. A digital marketplace is a lot more efficient, obviously, and transportation margins are very thin. Any little thing that can give us some more efficiency is going to be positive.

What is IoT? For our industry, it's connected sensors on everything, equipment, personnel, robots and drones, even freight on the pallets, containers, SKUs, even the infrastructure that we're driving around or meet up against. There are a lot of tailwinds driving IoT. The devices are getting cheaper, more efficient, and have better battery lives. They also have a lot more communication opportunities. It’s rare to see a facility that is loading or unloading freight that doesn't have a WiFi or cellular service. Along most major highways, you have pretty good coverage. IoT doesn't necessarily need constant coverage. It can go dark. Then when it comes back in the light, it can send its backlog.

Big Data and AI machine learning are basically two sides of the same coin. You have all these Big Data sources now—no human being can absorb or process that data. You need technology to process the data, particularly because a lot of it is not structured. It can be video images, for example, and there are new algorithms and breakthroughs in those areas. We like to bring all those things together: Internet of Things, Big Data and AI, and we agree with survey participants who think that these present the biggest opportunities for competitive advantage.

To discuss disruption in freight transportation with Steve, contact us.